__ MusiMatrix (eersteklasconcerten)

![]()

![]()

IDEA

MusiMatrix (eersteklasconcerten)

by Musica Impulse Centre for Music Belgium

Featured ensembles:

DuoBaan (B) https://duobaan/

Jasper & Jasper (B) http://jasperandjasper.be/

UMS 'n JIP (CH) http://umsnjip.ch

Works performed by UMS ´n JIP:

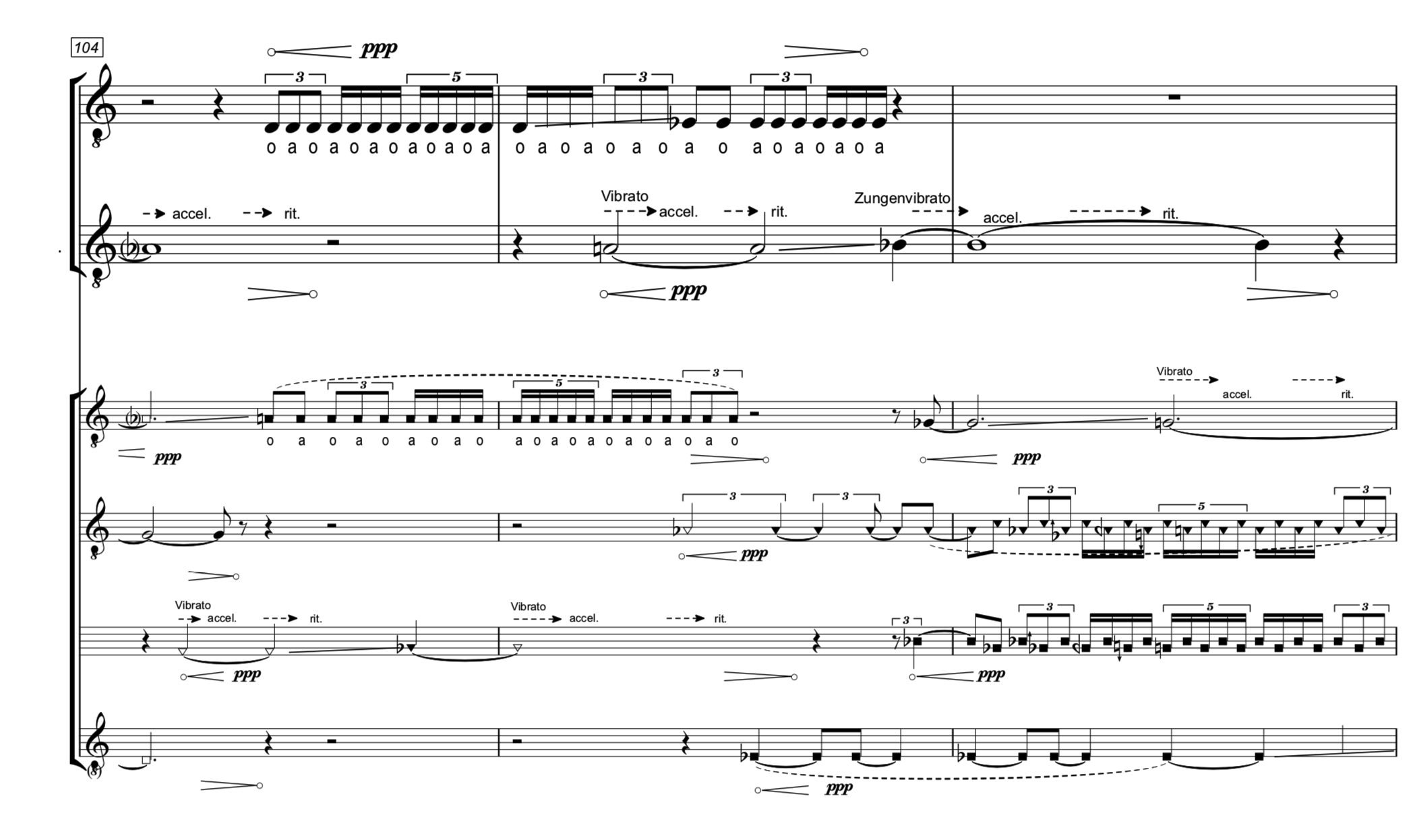

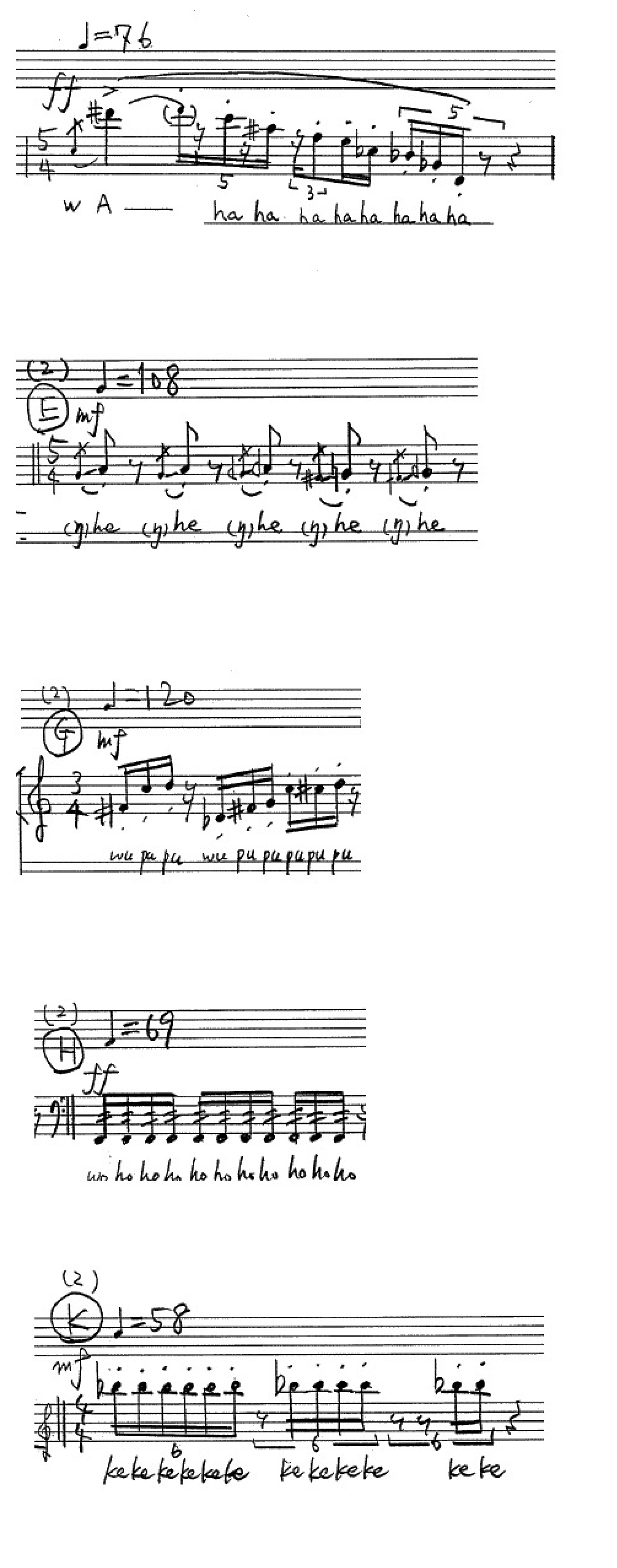

UMS 'n JIP - from: Sancho (electropop opera), 2019, Scene V

Motoharu Kawashima - Das Lachenmann IV, 2017

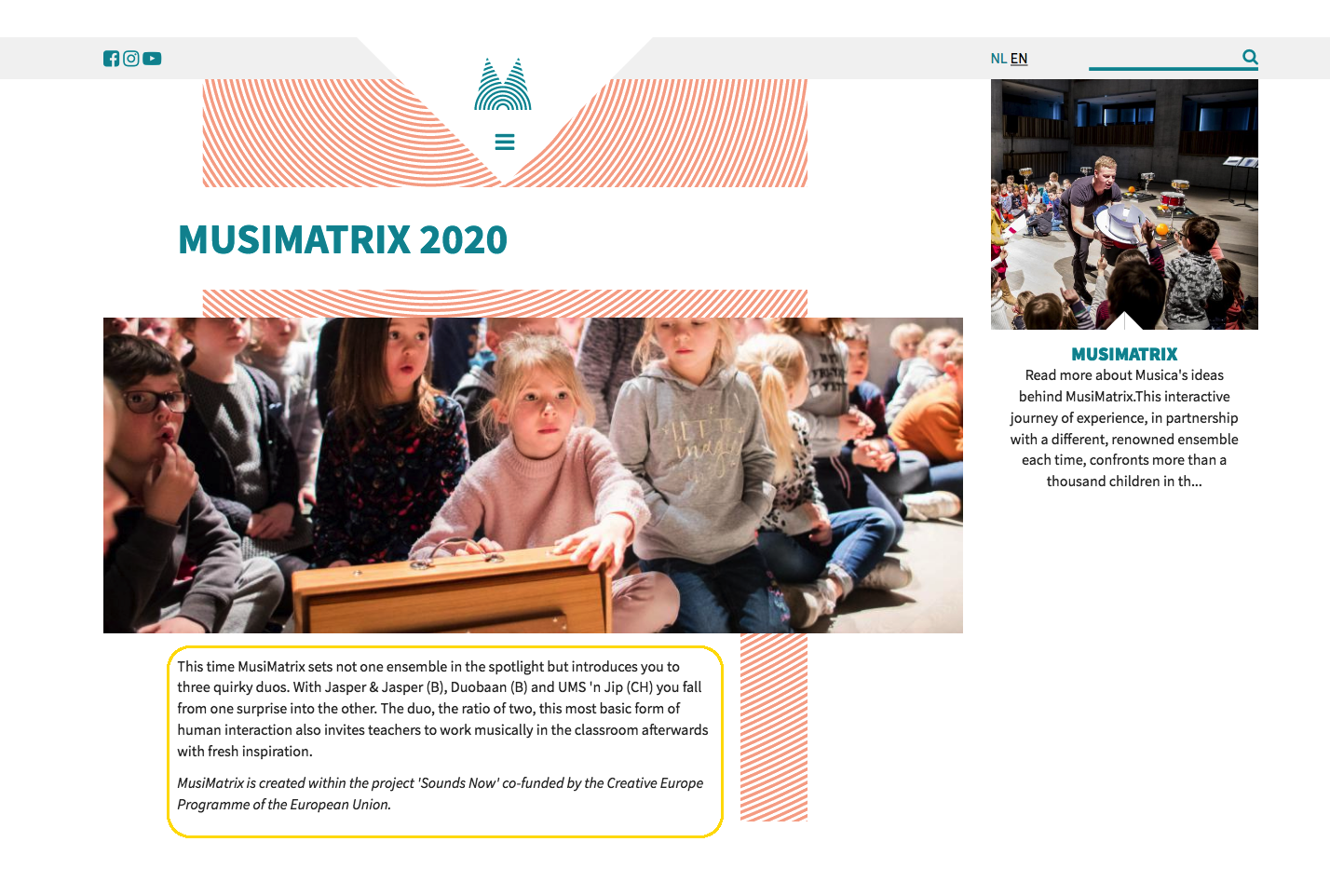

MusiMatrix (Eersteklasconcerten) is an interactive journey of experience confronting >4000 children in their first year of school with classical or contemporary composed music and its interpreters. These ‘first class concerts’ break down the borders between listening, active experience and performing together. The format was awarded a European YEAH! Award in 2015. From the jury report: “MusiMatrix is a unique, immersive experience for first grade students to become familiar with the sounds and process of contemporary music. The project epitomises the very essence of creating and playing music. All communication takes place via music, sound and movement. This is an ideal example of contemporary music mediation that relies on the motivation and activity of a young audience as well as the musicians – without reducing the artistic quality. Excellently done!” MusiMatrix/Eersteklasconcerten 2020 introduces you to three quirky contemporary music duos: Jasper & Jasper (B), Duobaan (B) and UMS 'n JIP (CH, performing works by Motoharu Kawashima/Das Lachenmann IV and excerpts from UMS 'n JIP´s acclaimed electropop opera Sancho). MusiMatrix 2020 is created within the project 'Sounds Now' co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. The project ‘Sounds Now’ has been selected as a large-scale European collaboration project for Creative Europe. Musica Impulse Centre for Music Belgium will lead Sounds Now, as project leader, together with: Wilde Westen (BE), Festival van Vlaanderen (BE), SNYK National Centre for Contemporary Music and Sound Art in Denmark (DK), SPOR Festival (DK), Viitasaaren Kesäakatemia ry (FI), Stichting November Music (NL), Stiftelsen Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival (NO), Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (UK) and Ariona Hellas AE (GR).

![]()

by Hans van Regenmortel

Musica Impulse Centre for Music Belgium.

Bringing New Music to New Audiences

Eersteklasconcerten: a new perspective on

contemporary music

participation of young children in concert halls

Contemporary composed music is often considered as too

abstract or too complex for young children. Nevertheless, it

is questionable whether ‘abstractness’ is a feature of the

music in itself. Then what would it mean? That the music

isn’t ‘about’ the real world? That it doesn’t ‘describe’

reality? Most music does not, even if one can imagine that

it reflects aspects of reality. And as complexity is

concerned, children are faced with all kinds of complexity

from birth. Why then avoid complexity when dealing with

music? Music that is being perceived or thought of as

abstract, rather refers to the lack of experience with an

idiom or its performance practice. In fact, the only

abstract music that exists, is the music we can’t imagine or

remember (Strobbe & Van Regenmortel, 2012), or the one

that lacks contextual anchor points with one’s own

experience. Then, how can a concert hall confront young

audiences with high level contemporary music and its

performers? Each year, Musica, Impulse Centre for Music

(Neerpelt, BE) and Concertgebouw Brugge (Bruges, BE) take up

this challenge with Eersteklasconcerten.

Organising a context for young ears

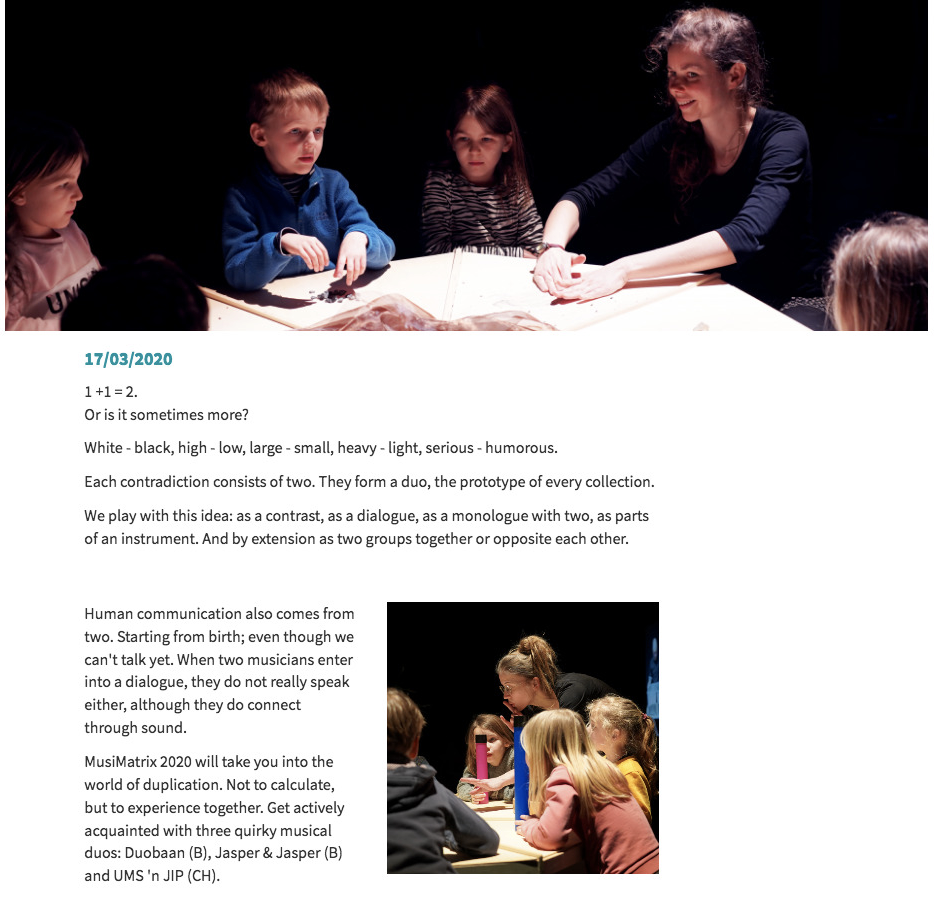

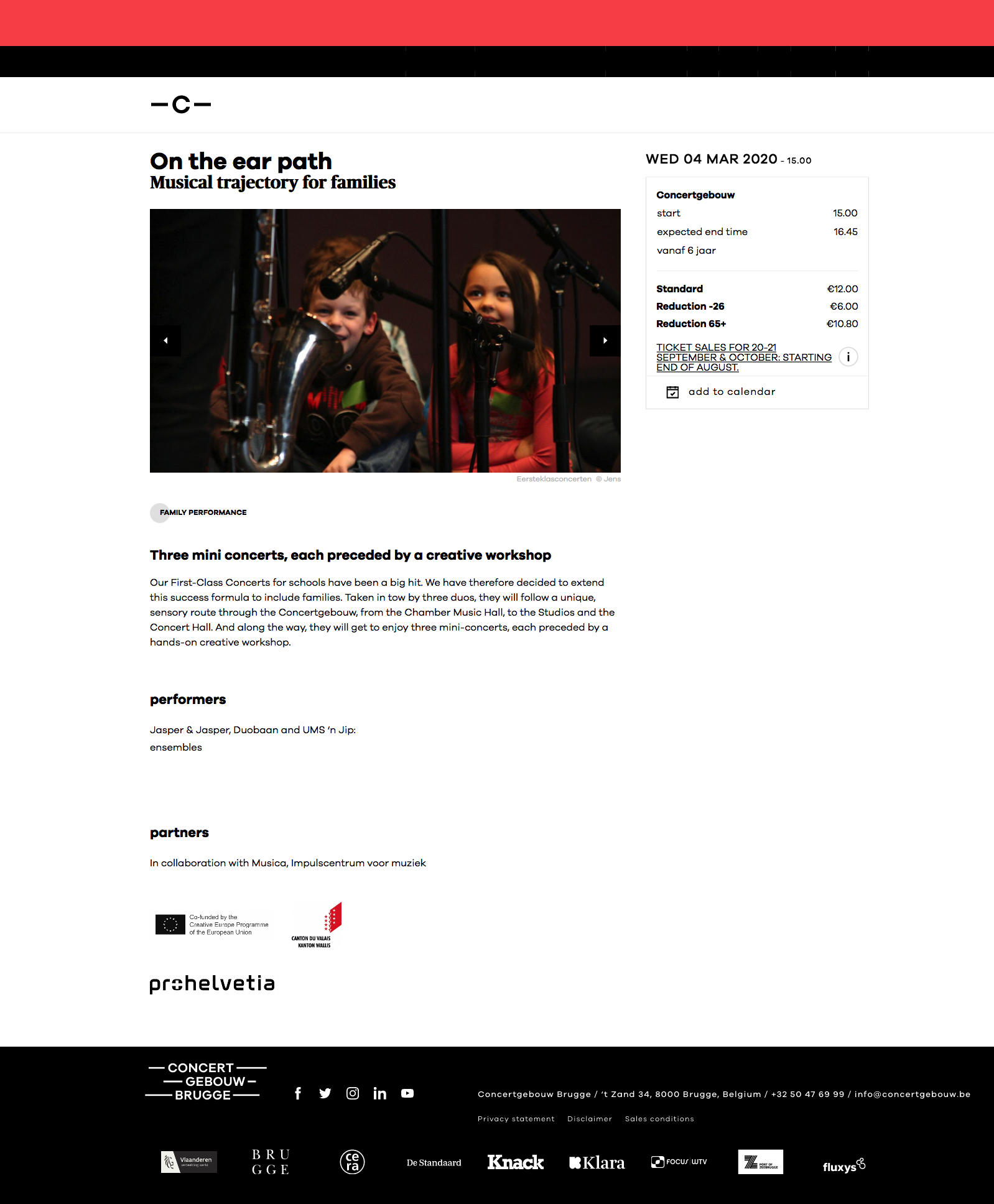

Eersteklasconcerten is an immersive journey of artistic,

interactive experience for children in their first grade of

primary school (in Flanders, this means 6 years olds). This

production puts a different renowned ensemble in the

spotlight each time, confronting young ears with

contemporary music and its interpreters, without

compromising on the artistic content. Eersteklasconcerten

addresses groups of 150 children, that become divided into 3

subgroups. The whole journey features an introduction,

followed by 3 parallel ‘stations’ - each consisting of a

mini-workshop and a mini-concert in whatever combination -,

and ends up with a performance that actively involves

everyone: children, musicians, Musica-teachers and school

teachers. Eersteklasconcerten lasts no less than 90’.

Nevertheless, the children manage to keep a substantial

level of attention without problem, absorbing music that for

many adults (e.g. their classroom teachers) isn’t always

obvious at first sight. Up to three journeys can be

organised in one day. The format can easily be adapted to a

family public as well. The introduction moment results in an

immediate focus and sharpened expectations. A general theme

is implicitly being introduced: e.g. ‘direction and timing

of sound’ (2017 ChampdAction), or ‘overlap of musical

layers’ (2018 Het Collectief). Then, the children go to

their respective first station divided in 3 groups of 50

children, each group following its own order of consecutive

stations. A station (approximately 20’) consists of any

combination of a mini-workshop and a mini-concert. The theme

pops up on each spot as an additional anchor point for an

emotionally connected understanding of the music.

Preparations start with a discussion about a program that

reflects the artistic DNA of the ensemble. The program

should make sense in its own right, regardless of its

complexity or artistic niche, nor the specificity of the

target group. At this stage, there is no concern whatsoever

about the design of the workshops. Only elements that could

serve as a program thread are possibly taken into account.

The only criterion in respect to the children’s age, is the

timing of the different compositions in favour of a careful

balance between listening and active engagement. How is it

possible not to compromise on the artistic level when

dealing with contemporary composed music? How do we tackle

the lack of experience and familiarity with a musical idiom

that - at first sight - is far away from children’s

experiences? How can we make these unknown musical idioms

meaningful on the spot and with only limited time?

Breaking down borders

Young children can make sense of the world in all its

complexity on their own terms, without any need for

explanation, provided that the context makes sense and that

the adult’s expectations are fluid. When children feel

emotionally connected with what is happening, this reflects

a ‘first level’ proof of understanding. A salient feature of

Eersteklasconcerten is the absolute lack of verbal

instructions and explanations. At each station the

Musica-teachers (sometimes assisted by trainees) only

communicate by means of body language and facial expression.

The spot itself communicates as well, as it is organised in

a clear and inviting way, containing minimalistic theatrical

elements. Borders between listening, active experiencing and

performing are broken down, all of them being historically

evolved adult distinctions of possible engagement with

music. This doesn’t mean that there is no listening in the

traditional sense. On the contrary! Young children can

listen in an astonishingly focused way, because the

listening is contextualised by what happens before, after or

along with the music. The children’s level of attention and

involvement is a main concern as it reveals their ‘sympathy’

with what’s going on. The distinction between a performer on

stage and listeners apart isn’t taken for granted anymore,

nor is it avoided.

Possible relationships between performer and listeners are,

for example:

● the listeners sitting or lying on the ground around the

performer

● the performer walking through the audience while playing

● all performers making a circle around the public

● the children moving or dancing while the musicians play

● the children making music together with the musician

As the specific focus on the music itself is concerned,

there may be a shift from its structural properties to

timbral, spatial and contextual aspects according to the

opportunities for sympathic engagement they provide. Or, all

of this can be left to ‘the ear of the beholder.’

Making music tangible in the literal sense

Young children have no need for ‘replicating the same.’

It’s already enough in having them perform something alike.

Precisely the result of this ‘relative approach’ is proof of

their musical intelligence: they recognise similarity. As

the music itself is technically too demanding for them to

replicate even part of it, we focus on more general

elements, which they are immediately able to grasp in the

literal sense. These aspects often feel familiar from

non-musical contexts, such as direction of sound, time,

chance, expectation, surprise or any combination of these.

Listening to a concert after a workshop, gives children the

feeling - even the conviction – of having invented the music

by themselves. Whispers like “That’s what we just did!”, “I

get tears in my eyes”, “I want to stay here”, are proof of

their basic understanding as well as the expression of

unique experiences on the personal level.

An embodied and shared experience

Although most children grow up with music coming from

loudspeakers without the presence of live musicians, this

situation masks the fundamental origin of music as a live

interactively shared phenomenon. Seen from the classical

performance practice, making music an embodied shared

experience could sound uncomfortable or unrespectful. In

fact, it isn’t. Let’s not forget that the ‘traditional’

concert practice mainly originated as late as in 1897 when

Mahler, as director of the Wiener Hofoper, “codified the

etiquette of the modern concert experience, with its

worshipful, pseudo-religious character.” (Ross, 2007). So,

we can ask ourselves to what extent approaches in which the

social and embodied aspects of music become more central and

visible again, are really new? Although the principle might

be not so new, the forms it can take surely is:

Eersteklasconcerten transforms and adapts old traditions to

new contexts and audiences.

Children as actors in a contextual whole

In Eersteklasconcerten not just each station but the

whole journey is seen as an artistic creation in its own

right. Yes, a spectacle, but one that avoids the

spectacular. It chooses for a sensitive approach, with sober

theatrical elements that enhance the musical experience. The

participants are no concert visitors, but actors that in

realtime appropriate themselves with essential aspects of

the music and its performance practice. In the other

direction, the performer’s interpretation has lost its

relevance in the traditional sense (Hamel, 2016). Important

is how the music is construed in the participant’s momentary

experience, and in the way the performer feels connected

with his audience. Not so much the music as an object stays

central, rather its impact and invitation towards reciprocal

active involvement. The musical composition becomes alive as

part of a wider whole. As part of the journey the

displacements from one station to the other are mapped out

as little moments of transition and relief. Within limits,

on these moments children verbally interact about their

experiences and express their feelings towards each other.

Conclusion

Eersteklasconcerten convincingly shows that, as long as

the context is well thought of, young children can get

really enthusiastic about contemporary music irrespective of

its artistic complexity. The format challenges the

interpreters’, concert organisers’ and school teachers’ view

on children’s aptness to ‘understanding’ contemporary music.

Furthermore, it challenges the idea that children need a

methodological approach from simpleness to

complexity. Eersteklasconcerten illustrates children’s

sensitive openness and aptness for being part of a

contextual whole. The format makes us aware of children’s

need for symbolic play in a context of shared experience and

companionship as a basis for being educated.

References

Strobbe, L. & Van Regenmortel, H. (2010).

Klanksporen: Breinvriendelijk musiceren.

Antwerpen/Apeldoorn: Garant Uitgevers.

Strobbe, L. & Van Regenmortel, H. (2012). Music Theory

and Musical Practice: Dichotomy or

Entwining. In Dutch Journal of Music Theory, 2012, Volume

17, Number 1, 17-28. Amsterdam:

Amsterdam University Press.

Hamel, M. (ed.) & van Maas, S., van Weelden, D.,

Luijten, A. (2016). Speelruimte voor

klassieke muziek in de 21ste eeuw. Rotterdam: Codarts.

Ross, A. (2007). The Rest is Noise: Listening to the

Twentieth Century. New York: Picador.

Van Regenmortel, H. (2017). Eersteklasconcerten: a different

look at music participation of

children in concert halls. In Pitt, J; & Street, A.

(ed.). Proceedings of the 8th Conference of the

European Network of Music Educators and Researchers of Young

Children. Cambridge:

EuNet Meryc.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1R2g8iuV4FmNYKjrQ-mO2eM9PvKYui0qr/view

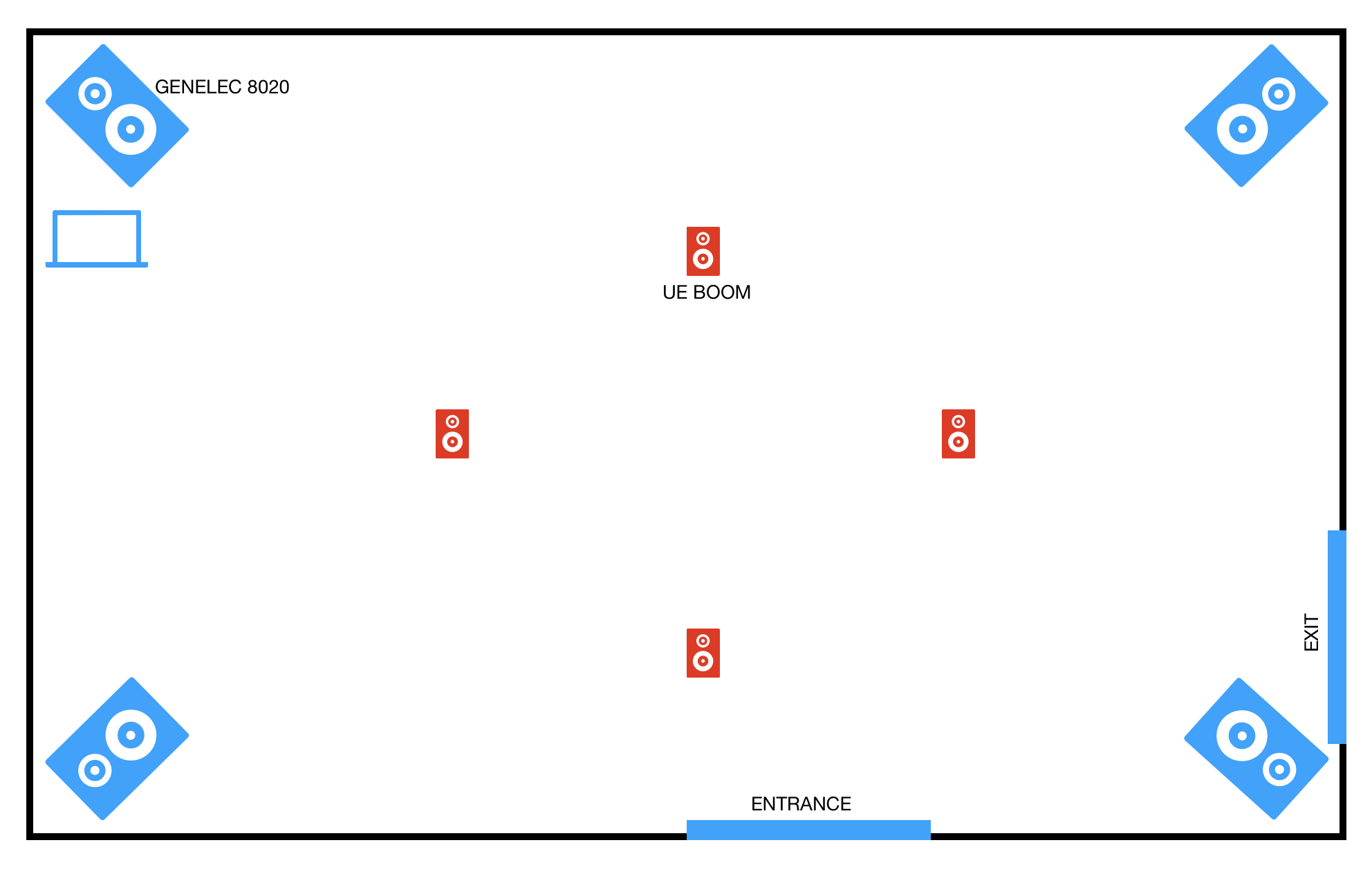

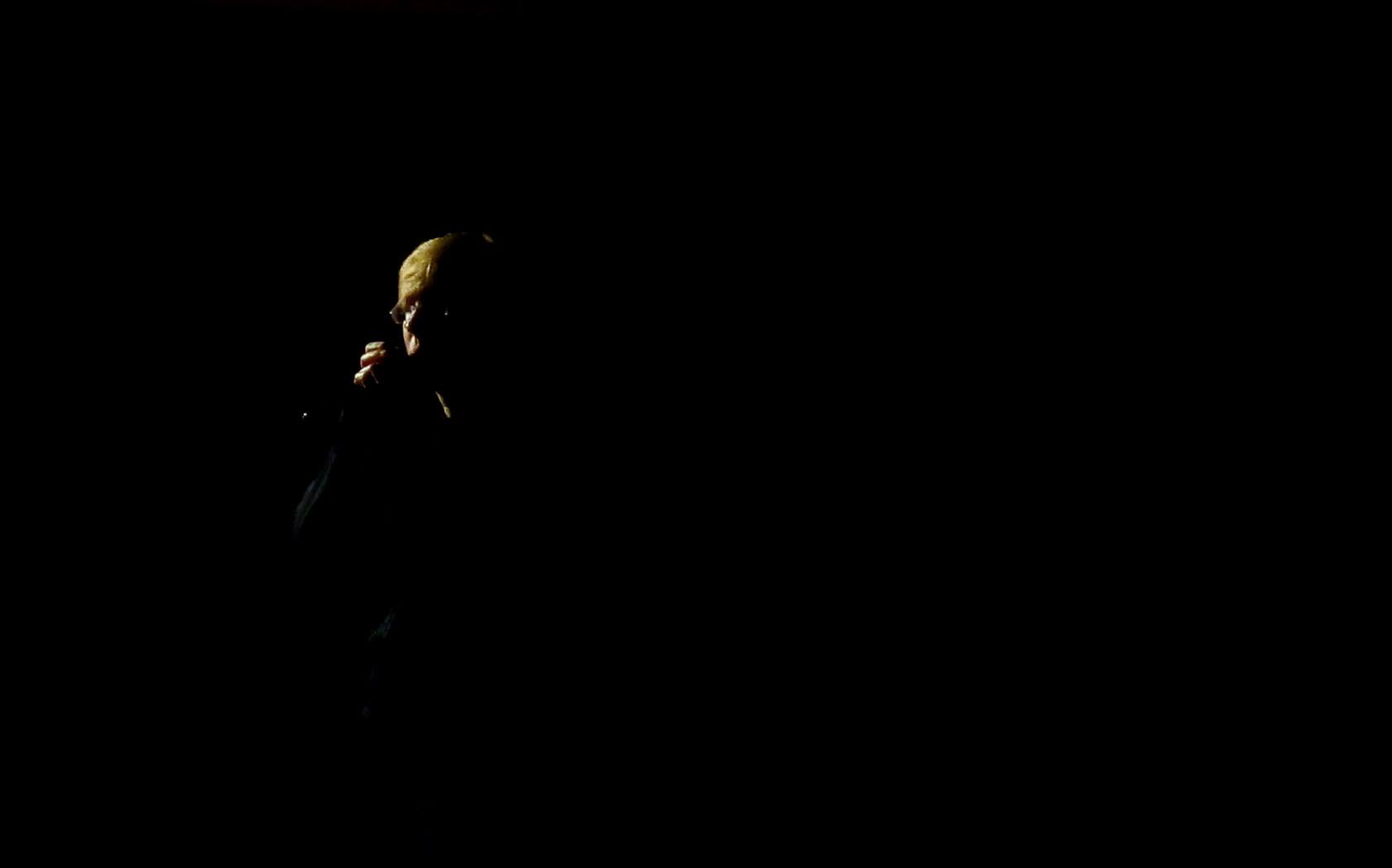

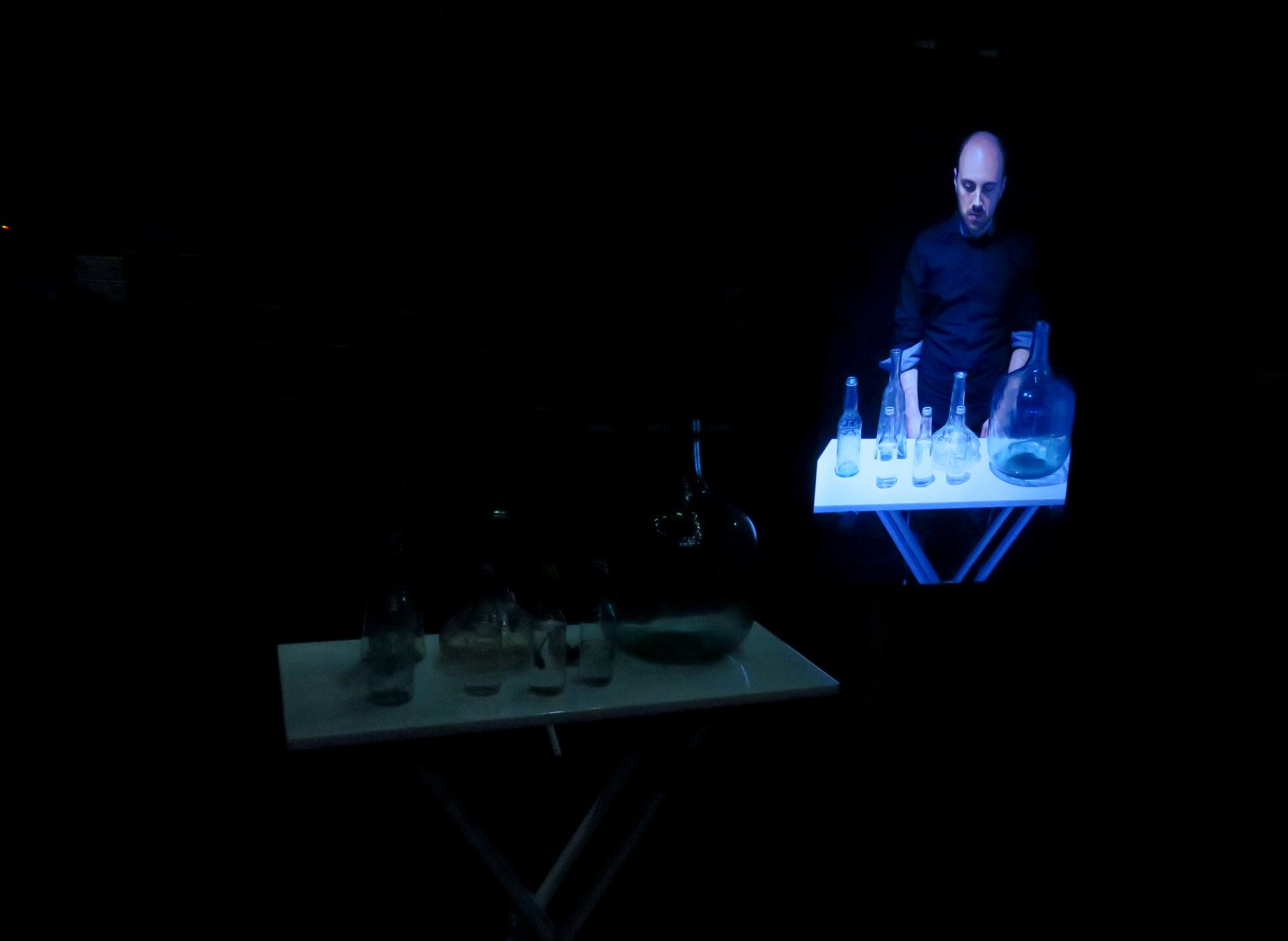

![]()

UMS ´n JIP, MusiMatrix 2020, audio setup

Die für MusiMatrix 2020

(eersteklasconcerten) entwickelte Performance integriert

zwei Werke: die Szene V (Merlin) aus UMS ´n JIP´s

electropop Oper Sancho (2019) und das dem Duo gewidmete

Werk Das Lachenmann IV von Motoharu Kawashima aus dem

Jahre 2017. Sie dauert etwa 20 Minuten und ist szenisch

einem Tagesablauf nachempfunden: Die Zuhörer betreten den

Raum bei Nacht, legen sich zum Schlafen hin und erwachen

bei Sonnenaufgang. Sie stehen auf, sobald die Sonne im

Zenit steht und ruhen bei Sonnenuntergang wieder. Der

Sonnenverlauf wird mittels Lichtregie inszeniert. Es

spielen UMS und JIP, unterstützt von zwei Musica-Lehrern

als Animatoren. Die Zuhörer befinden sich in einem

Doppelakusmonium. Vier Genelec 8020 sind in den vier Ecken

des Raumes aufgestellt, in der Mitte des Raumes befindet

sich ein weiteres Lautsprecherquadrat mit vier

omnidirektionalen UE Booms, damit ist eine gleichmässige

Klangverteilung im Raum gewährleistet. Alle acht

Lautsprecher befinden sich auf 1m Höhe (der approx.

Ohrenhöhe der Kinder). Die Kinder betreten den

verdunkelten Raum und bleiben in der Mitte desselben

stehen, äusserst leise sind Atemgeräusche und

Labium-Frullati aus den UE Booms zu hören: diese Klänge

und Geräusche mischen sich unmerklich mit live gespielten

Geräuschen zu einer zarten und zerbrechlichen

Klanglandschaft, welche aufmerksames Zuhören verlangt. Die

Kinder legen sich hin, alsobald startet die Szene V aus

Sancho, das äussere Akusmonium schaltet sich zu, der Raum

wird nun in seiner vollen Grösse bespielt. Die Parts von

UMS und JIP integrieren sich in das Zuspielband derart,

dass ihre Ortung nicht mehr eindeutig ist, ein Spiel mit

Realität und Fiktion beginnt. UMS spielt in der Mitte des

Raumes, JIP schreitet singend an den äusseren Rändern des

Raumes entlang. Die Szene V aus Sancho etabliert zunächst

Einzeltöne und Geräuschimpulse, welche mit Stimme und

Blockflöte erzeugt werden. Die Klanglandschaft erinnert

von Ferne an Geräusche im Gehölz. Die Knack- und

Zischlaute verdämmern allmählich, die Töne verdichten sich

zu Akkorden, zunächst zu Terzen, danach zu instabil

intonierten Dur- und Molldreiklängen, welche sukzessive

nach oben gleiten. Allmählich werden die Kinder

aufgefordert, diese Klänge zu imitieren und sich

individuell wie in Gruppen in die Klanglandschaft zu

integrieren (die

Klänge der Szene V lassen sich mit der Stimme und den

Händen (Schnalzen, Schnippen, Summen, Pfeifen) leicht

kopieren). Am dramaturgischen Höhepunkt dieser

Szene bricht bei Minute 12 ein Lachen ein, die Szene V aus

Sancho wird ausgeblendet. Verschiedene Lacher, welche

motivisch mit dem Stück Das Lachenmann IV verknüpft sind,

werden etabliert und von den Kindern spielerisch

nachgeahmt. Danach wird Das Lachenmann IV gespielt. Lachen

ist in unserem sozialen Umfeld mit Spontaneität

assoziiert. Lachen kompositorisch bzw. als musikalisches

Strukturelement zu verwenden führt den Zuhörer in eine

reizvolle Grauzone, weil es den Grenzbereich von Klang und

Bedeutung auslotet und mit grundlegenden Erwartungen

innerhalb unserer Kommunikations-Codices spielt, indem

emotionale Ausbrüche (in diesem Werk in Form eines

Lachens) formal und klanglich in eine Komposition

eingebunden werden. Das Kompositions- und

Performancematerial wird über die Aufführungen hinaus

unterrichtsgerecht aufbereitet. Die Schullehrer erhalten

Übungsblätter, um das Erlebte spielerisch nachzubereiten,

weiterzuentwickeln und nachklingen zu lassen.

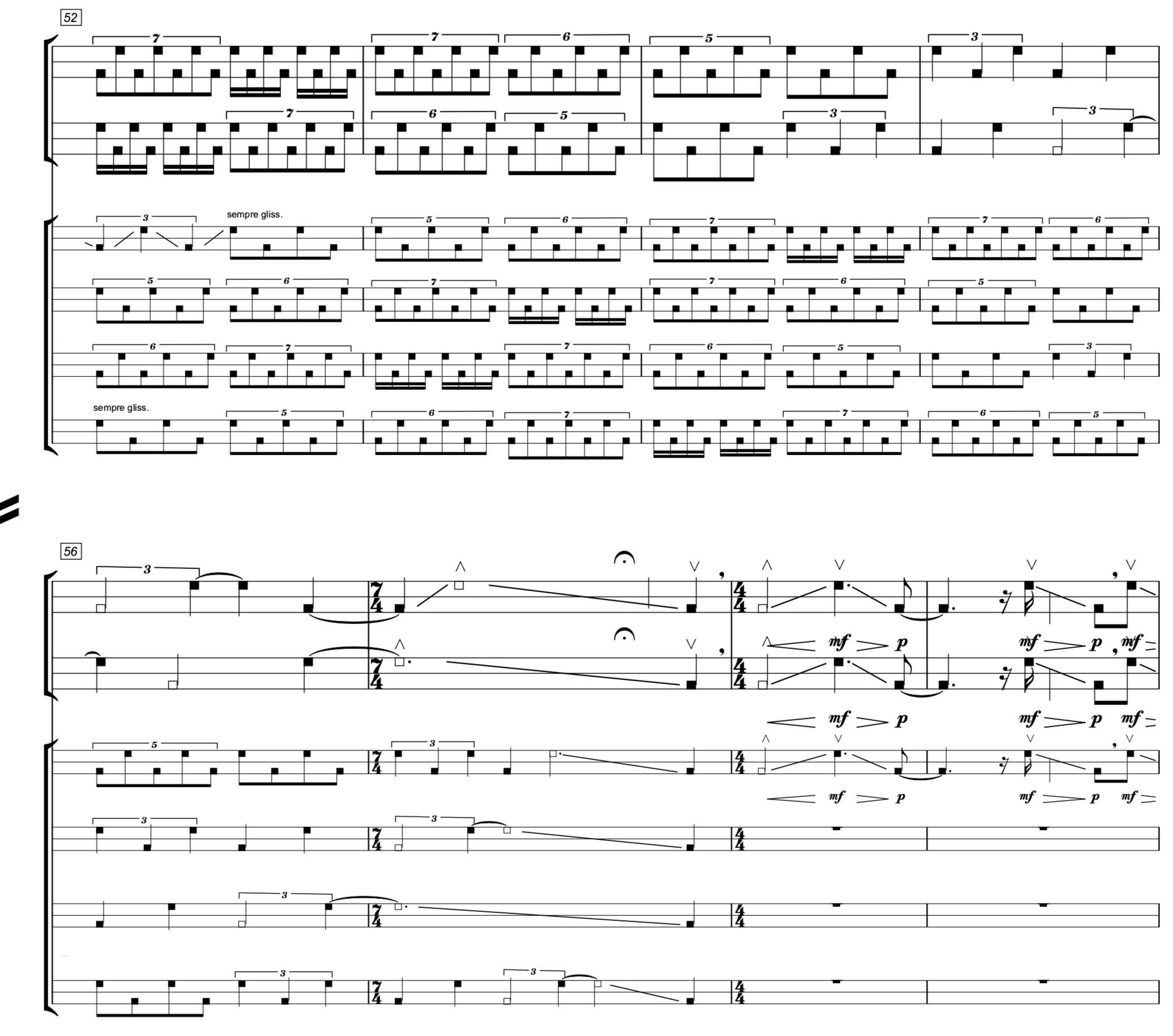

UMS ´n JIP

score excerpts from Sancho, Scene V

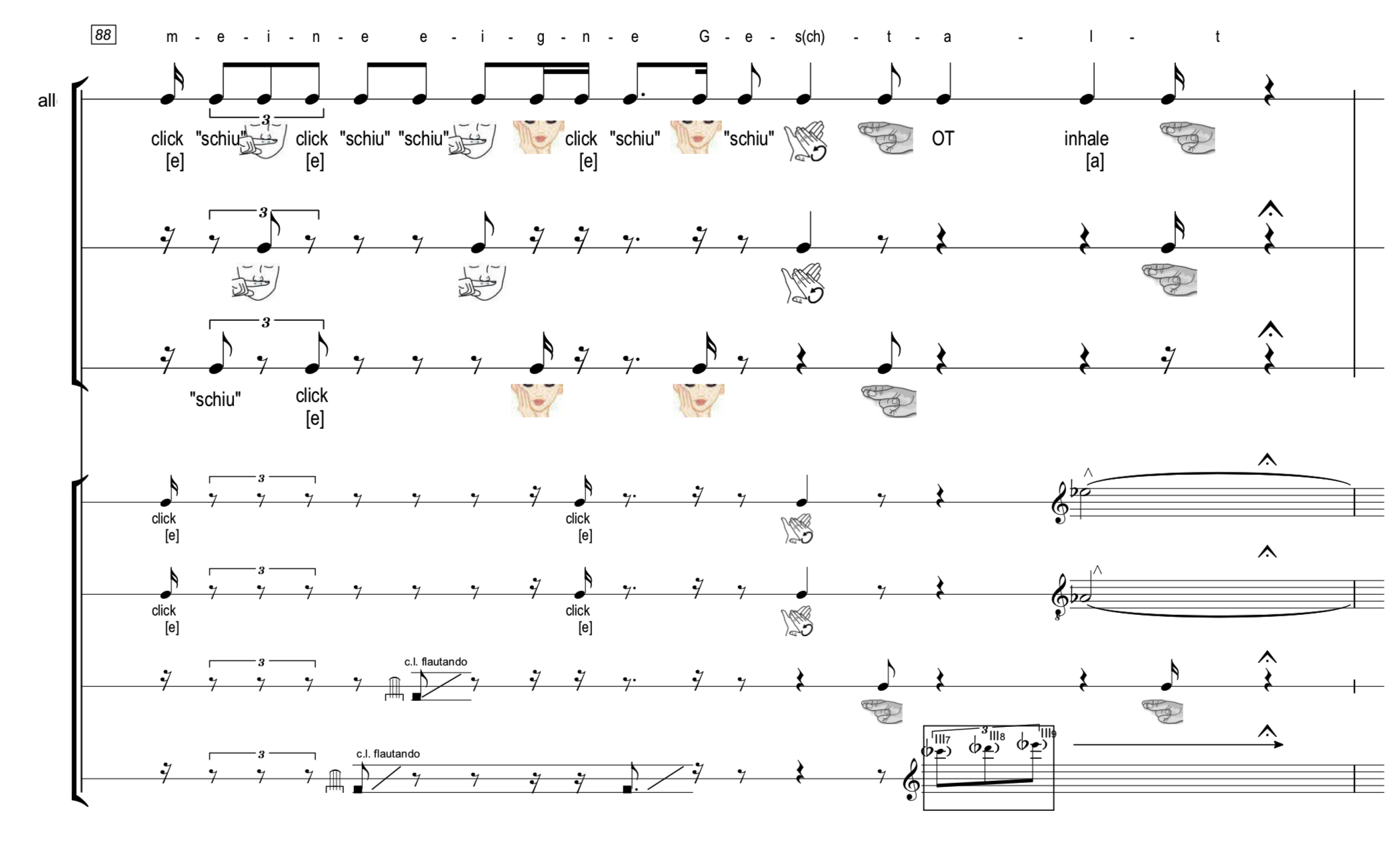

Motoharu Kawashima

score excerpts from Das Lachenmann IV

![]()

![]()

![]()